The Neverending Story, Part 1: Intro and History

“Afterthoughts” is a new Fear of God blog series featuring co-hosts and guests further unpacking thoughts, themes, and ideas that keep them up at night from the conversations and content covered on the show. This entry is by recent guest, Dave Courtney, and is part 1 of 4 of a follow-up article series to this week’s episode featuring The Neverending Story. Enjoy, then, this latest entry in the new chapter of The Fear of God…

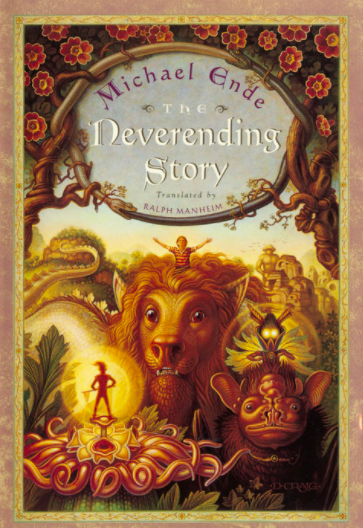

During the official Fear of God podcast episode for Wolfgang Peterson’s adaptation of Michael Ende’s The NeverEnding Story, it was acknowledged that there were multiple other areas and ideas we could have explored in what likely could have resulted in a good many more hours, if not days, worth of discussion. I am grateful for the opportunity this afterthoughts blog series affords for exploring a few of these untended threads.

As my choice and personal submission for the current “what scares us” series, it goes without saying that the following thoughts reflect my personal experience with the film along with some of my fresh takeaways from our podcast discussion, particularly in terms of further fleshing out the different ways this film spoke to me as a child and again in my adult years from a fresh and renewed perspective on God and life.

In our discussion we touched on the idea of these two separate worlds represented in the film, the imagined world Bastian discovers in the pages of this book (Fantasia, or Fantastica as it is named in the book), and the real world that Bastian occupies in his life at home and at school. I noted how one of the key ways this film spoke to me was in its exploration of these two worlds being posited as a working tension, between the way the world is and the way we desire (or imagine) the world to be. In the film this is what the idea of Fantasia and the eternal nature of the Emperor is meant to evoke, this picture of worlds once united now divided, and as a young child the idea of Fantasia as something that could invade my world “as it is” through what I understood to be the “Christian” imagining of what the world “actually is” and can be came most alive for me in my love and engagement of story. If imagination can also be understood in the Christian Tradition as desire or hope, this notion of the “Christian” imagination holding the power to enact faith in something greater than myself and my present reality allowed me to learn to trust in this faith-filled idea that what is wrong will somehow be made right, empowering me then to participate in the act of bringing about this imagined change in the world around me through my willing participation in this story. For as much as I could not change my circumstances as a young child, something I speak to more specifically in the podcast episode, this film captures this continued conviction within me that there is a way In which I can begin to see and exist in this world differently.

Full confession: as I grew into my adult years, my ability to reconcile my experience of the world I knew with the world I hoped for became increasingly tough. In the podcast episode I mentioned a book in the “whatcha” section by Biblical Scholar N.T. Wright called History and Eschatology: Jesus and the Promise of Natural Theology, a book that I suggested might intersect with our conversation about the film at some point in a meaningful way. Since I failed to do so in the actual conversation, I figured I would bring it back up briefly here.

This book is based on a set of lectures Wright gave for the 2018 Gifford Lectures, and in it he offers some helpful insight towards this idea of bringing the two divided worlds of The Neverending Story together within the unifying nature of the Christian narrative, particularly for those of us in the West who have long been conditioned to see the natural world and theology forever at odds. Speaking of the movement towards modernity and Western development that we can observe in the enlightenment of the Eighteenth century, he writes:

“The easily assumed divine Jesus of the then Christian orthodoxy, and the equally easily assumed ‘divine inspiration’ of scripture, meant that appeals to either were seen by the devout and the sceptic alike as settling the question in advance. No real historical work was required, and indeed to propose such a thing might be taken (as it still sometimes is) as a sign of infidelity to the gospel, a collusion with an implicit denial of God. The ‘natural’ and the ‘supernatural’ worlds were split apart, with those words themselves changing their meanings so as to support just such a complete disjunction… In (this) split level world of the modern Epicurean revival, with the gods and the world divided by a great gulf, it was bound to appear that Jesus must belong on one side or the other, but not both.” (taken from the preface, pages xv and xvi)

THE NEVERENDING STORY OF ENDE’S GERMAN UPBRINGING AND THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Understanding the historical context which informed author Michael Ende’s creation of the Neverending Story can allow this notion of two worlds “split apart” to speak to his own need to use The spiritual, and likewise Christian, imagination as a way of imagining a different reality. Ende grew up in Germany, eventually being shaped most readily by the reality of the Second World War and the rising force of fascism and empire. His father, also an artist, was rejected and oppressed by the regime, and he watched helplessly as his own knowledge and experience of this seeming disconnect between the way the world was and the way he hoped the world to be seemed to declare it irreconcilable.

One of the things we can observe in Ende’s book is his own noted critique of modernism (with foreshadowings of post modernism) as an answer to the problem. We see this in the way he establishes the limiting nature of science and reason and progress (represented most readily in the charming characters of Engwook and Urgl), and even ourselves (Atreyu and the Rockbiter come to mind) to provide a true answer to the problems we observe within the present state of this world, something that would have seemed only all to real for Ende. As well, the charge in the film for Bastian to “keep his feet on the ground” and “get his head out of the clouds” expresses the very real struggle of existing within this split-level view of the world that modernism represents and upholds as Bastian both faces the reality of his world and hopes for a better one to somehow emerge within his own imaginative process and his obvious love of story. This is what brings him to the dangerous nature of engaging with the neverending story.

What’s interesting to me is how you can see all of this, too, in Ende’s inclusion and fusion of both Eastern (for example Falkor, who in the book has a much more definitive Japanese character, with his name being translated fukuryu, meaning luck dragon) and Western myth (Atreyu being imaged after the indigenous peoples of the Americas). This gives way to the sharp religious and spiritual imagery where we see Fantasia and the real world gradually coming together over the course of the larger, unfolding story, both for Bastian and Atreyu and also for us as readers and viewers. It is within this that I think our discussion in the podcast episode of the Temple as the “place” where Heaven and Earth meets (and the Sabbath as the “time” in which this then plays out as the promised new creation) becomes a fruitful picture for our own reconciling of both struggle and hope within the Christian experience.

MORE FROM DAVE IN PART 2, TOMORROW!